Why the Online Safety Act must be repealed

Britain doesn't do firewalls. Or at least, it didn't.

In a country that once prided itself on free speech, limited government, and an instinctive distrust of state overreach, the Online Safety Act is a stain. Introduced under the guise of protecting children, the law has delivered instead a Frankenstein’s monster of bureaucratic censorship, data harvesting, and digital control. It is not only unworkable. It is un-British.

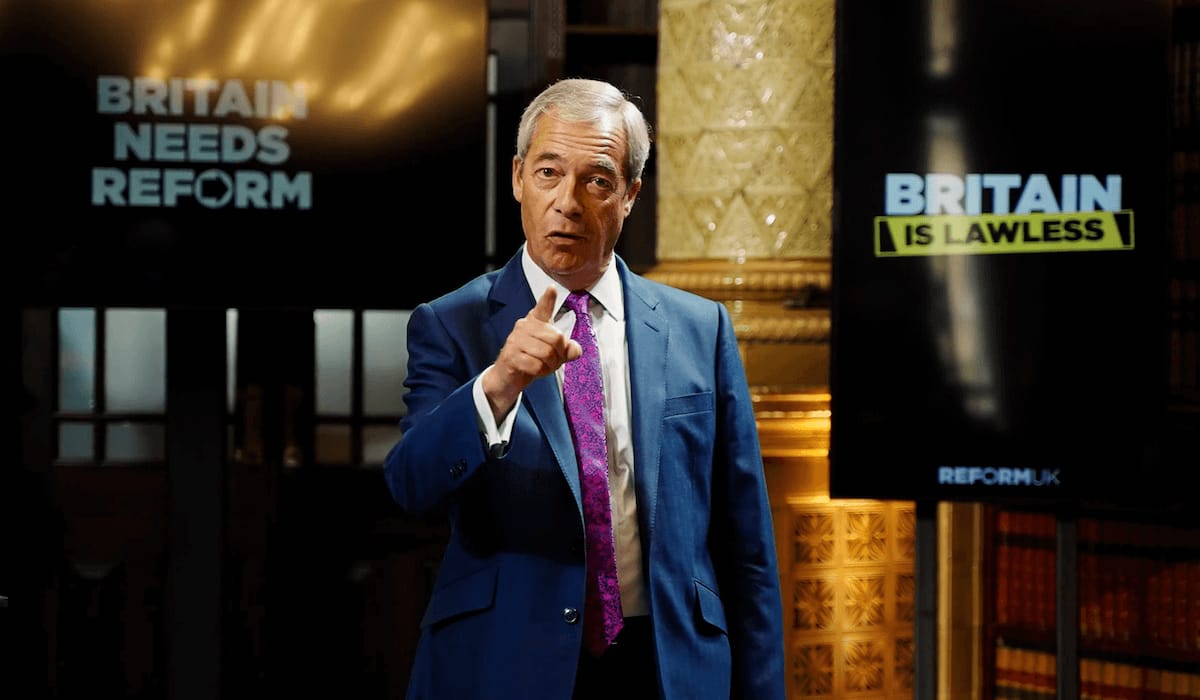

This week, Reform UK vowed to repeal the “borderline dystopian” legislation. They’re right. But repeal isn’t enough. The Act should be studied as a warning: how easily the language of safety becomes the language of control.

When the age verification powers kicked in on 25 July, the British public responded with quiet defiance. VPN signups surged 1,400 percent. Every major app store chart was topped by VPN services. Ofcom muttered about “compliance”, but the public had already issued its verdict: “No.”

Teenagers, parents, pensioners are all routing around the law. Why? Because Brits do not queue up to show their passports to browse the internet. They do not upload their faces to private firms just to access articles, forums or YouTube.

Instead, they downloaded Proton, Nord, Atlas - digital bolt-cutters for a government-imposed lock.

The Act grants Ofcom sweeping powers to regulate “legal but harmful” speech. Platforms must pre-emptively censor anything deemed distressing—on pain of billion-pound fines or even prison. The culture secretary can quietly update these definitions. Speech becomes policy. And policy is made in Whitehall.

No jury. No Commons vote. No transparency.

Meanwhile, the age verification regime outsources its snooping to unaccountable third parties. You’ll hand over your ID, your facial scan, your browsing history, not to the police, but to a “certified” private company. Data privacy? Gone. Due process? Gone.

Britain once fought wars over liberty. Now it outsources censorship to contractors.

Britain once fought wars over liberty. Now it outsources censorship to contractors.

If this creeping digital authoritarianism at least protected children, it might be worth the moral debate. But it doesn’t.

Teenagers are the most VPN-savvy generation alive. The result? Children still access harmful content, while the less tech-literate are locked out of legitimate sites. Worse, bad actors now lure minors toward sketchy corners of the web pretending to help them get verified. Fraud flourishes. Safety deteriorates.

The law punishes the innocent, misses the guilty, and drives the vulnerable into riskier spaces.

Reform UK now promises repeal. Their framing is correct: this law is an affront to free speech, a gift to the nanny state, and a chilling precedent for government control. But even they admit they have no clear alternative to protect children online.

We do not build Great Firewalls. We do not criminalise false opinions. We do not accept state‑mandated filters as the cost of protection. Or at least, we didn’t.

This is the trap. Once “safety” becomes the frame, liberty is always the casualty. Every new law becomes a new ratchet. Repeal is essential. But so is resisting the language that justifies this surveillance architecture in the first place.

Leader of Reform UK, Nigel Farage, promised to repeal the Online Safety Act

We do not build Great Firewalls. We do not criminalise false opinions. We do not accept state‑mandated filters as the cost of protection.

Or at least, we didn’t.

The Online Safety Act is a continental import masquerading as policy. It is the EU’s worst instincts and Silicon Valley’s culture-war puritanism rolled into one: algorithmic nannying enforced by faceless regulators.

Its repeal would not be a lurch into chaos. It would be a return to British norms: personal responsibility, limited government, and the presumption that a free people can navigate a free internet without state handholding.

If the Conservative Party had any spine, it would have repealed the Act before Reform even mentioned it. Labour, naturally, prefers control. The only question now is whether Britain still has a political class that remembers what freedom looks like or whether it’ll take another VPN surge to remind them.

When a government builds walls between its people and the open web, the danger isn’t what gets in.

It’s what’s kept out: dissent, scrutiny, freedom.